《TAIPEI TIMES》 Taiwan in Time: Thrown in ‘song jail’

Fong Fei-fei’s album Rose, Rose I Love You was released in December 1978, a month after her singer’s permit was suspended. Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei Times

During the Martial Law era, the government could, and often did, temporarily ban entertainers from performing in public by suspending their permits

By Han Cheung / Staff reporter

Nov. 9 to Nov. 15

The “Performing Artist Self-Regulating Review Committee” (影視劇演藝人員生活自律評議委員會) called an emergency meeting on Nov. 10, 1978. This entertainment industry “censorship board” was given a big case. Fong Fei-fei (鳳飛飛), one of the country’s most popular singers, had been accused of obscene speech and behavior during a concert.

It came as a shock to the public since Fong was known for her squeaky-clean image and, despite her claims of innocence, the government suspended for three months her permit to sing.

During the Martial Law era, not only could songs be banned, entertainers could be prohibited from performing as well. The authorities did this by suspending or canceling their permits to sing or act.

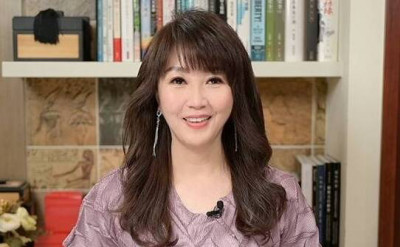

A notable case involved pop diva Yao Su-jung (姚蘇蓉), who had her permit suspended for two years in 1969 after being arrested while performing the banned song Heartless Person (負心的人). Dejected, she left Taiwan and continued a successful career in Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia.

Oddly, Heartless Person wasn’t even banned for language, political or obscenity reasons. The authorities simply found it too “emotional and despondent,” and would “negatively affect the spirit of the people.”

According to most accounts, however, Fong did not do anything suggestive. Rather, it was two male co-performers on stage who allegedly exhibited the “vulgar” behavior (they also claimed innocence) — behavior that was actually quite common.

Government censorship of the entertainment industry in those days was quite arbitrary and erratic, and historian Kuan Jen-chien (管仁健) examines several notable cases in his book series, The Taiwan You Don’t Know About (你不知道的台灣).

SELF-REGULATION COMMITTEE

In true censorship fashion, the permits were issued by city and county Departments of Education, since it really wasn’t about their performance abilities but rather how their behavior and material would affect the people and their allegiance to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). Applicants had to be elementary school graduates who were at least 15 years old, and had to pass a written exam and interview.

When the singers’ permits were suspended for whatever reason, people would say that they were in “song jail” (歌監), Kuan writes.

But back then, suggestive skits full of sexual innuendo helped to determine the popularity of public performances, especially in central and southern Taiwan. People were drawn to these shows because such antics were banned on television. Usually, the producers would submit a “clean” version to the government for inspection, and the entertainers would improvise their lines. As long as the venue owner had good connections and paid off the right people, they could get away with it, Kuan writes.

In 1976, popular entertainer Yu Tian (余天) and several others were arrested for their roles in an “obscene” play, and things escalated when Yu punched a reporter trying to snap a photo of him at the police station. The government suspended Yu’s permit for a year.

To clarify the rules, the Government Information Office that year gathered a dozen entertainment industry bigwigs and drafted the 10-point “Performing Artist Self-Regulation Convention,” which all performers were required to sign. They then had the various entertainment associations form the Performing Artist Self-Regulating Review Committee, which was in charge of punishing those who violated the convention. This treaty involved the performers’ private lives and physical appearances — one singer was suspended for six months for dating a married man.

Of course, that didn’t stop any of the “obscene behavior” as live venue owners continued to bribe the police, and the sexually-charged shows went on.

THE FONG DEBACLE

The immensely popular Fong’s “obscene” performance allegedly happened in September 1978, when she asked the audience for tips to gain weight, given her petit frame. Her two male co-performers allegedly made breast-squeezing and self-pleasuring motions in reaction to the audience suggestions of “drink more milk and drink more soymilk.”

Kuan writes that this was perfectly normal behavior in those days, yet Fong’s suspension shocked the nation due to her clean image. A devastated Fong wrote a long letter to several newspaper outlets claiming that she was innocent. The GIO refused to reverse its ban.

According to Kuan, the real reason for Fong’s suspension was that she rejected the advances of a high-ranking secret police officer. In the end, this incident actually boosted her popularity as rabid fans traveled to Taichung from across Taiwan to attend her first public appearance after the ban.

But Kuan notes that Fong’s behavior became markedly more “patriotic” after the incident, participating in overseas pro-government fundraisers and appearing at morale-boosting gatherings and military events. Her January 1982 concert was titled “Let the Three Principles of the People Fly Toward the Mainland Charity Show” (三民主義飛向大陸義演晚會), where she raised NT$3 million to help the suffering compatriots in China.

That same July, she released her 57th studio album, I Am Chinese (我是中國人), and Kuan writes that she never encountered any trouble from the government again.

Meanwhile, permit rules were already loosening by then. In March 1981, singers no longer required a permit to perform at restaurants, and gradually the number of applicants dropped, according to a Thinking Taiwan article.

Three years after the lifting of martial law in 1987, the government stopped issuing the permits. Although nobody actually needed permits to perform anymore, the law wasn’t formally abolished until 1997.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

新聞來源:TAIPEI TIMES

Yao Su-jung left Taiwan after her singer’s permit was suspended for two years. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons