《TAIPEI TIMES》 Dragon trees and ghost armies

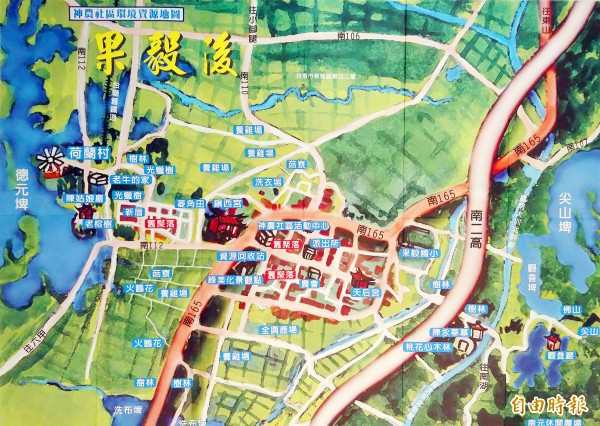

A map of community resources put together by the Shennong Community Development Association. Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Legends abound in the history-rich but remote village of Guoyihou in northern Tainan, and collecting and disseminating these stories is a major project for the Shennong Community Development Association

By Han Cheung / Staff reporter

Farmer Chang (張) was shocked when he woke up in a field to see a massive army doing military drills. He trembled in fear as a towering, stately man approached him on a magnificent steed and told him to never reveal to anyone what he had just witnessed.

Retired teacher and amateur historian Chang Chia-cheng (張嘉成) says it was likely that the farmer had seen the ghost of Chen Yung-hua (陳永華), the famed military adviser who helped Ming-dynasty warlord and pirate chieftain Koxinga (Cheng Cheng-kung, 鄭成功) expel the Dutch from Taiwan in 1662, as his gravesite was located near Chang’s farmstead.

The farmer’s wife, Chang Chia-cheng continues, became concerned as the once gregarious farmer became a brooding, melancholy man. She finally persuaded him to tell her what happened — and the next day he went blind.

Nearly a century later, farmer Chang’s grandson tells Chang Chia-cheng that his grandfather had indeed gone blind at some point in his life. The farmer’s story, and many others like it, are the kind that Chang Chia-cheng has been digging up for the past four years in an effort to generate community awareness in Shennong Borough (神農里) within in his native village of Guoyihou (果毅後) in rural northern Tainan City.

In addition to educational activities and beautification, a big part of the project is collecting legends and preserving the rich history of this remote and aging village.

“A place is memorable because of its people and their stories,” Chang Chia-cheng says. “From there, culture, customs and religion evolve as well as industries to support the various rites and rituals. This leads to religious troupes that provide entertainment or protect the village. It’s all connected.”

TRUTH IN LEGEND

Chang Chia-cheng has unearthed many legends, but one he grew up with is the Lord of the Five-Legged Pine (五腳松王公), which involves the dragon steed of the Buddhist goddess Guanyin (觀音). He had already told it once the night before with much enthusiasm, but it was worth hearing him repeat it again while driving through the pineapple fields and irrigation canals against the verdant hills where the story took place.

Chang knows how to tell a story, which takes on extra local flavor due to his Hokkien-accented (also known as Taiwanese) Mandarin. It was the early 1900s, and the dragon’s resting place at Foshan (佛山), just east of the village, was targeted by the Japanese colonizers to build a dam to support their sugarcane industry.

But no matter how much the forced laborers hacked into the earth, the next day the land would return to its original form. A rich man from a nearby village, who was jealous of the prosperity of Guoyihou, wanted the project to succeed as legend had it that damaging the dragon would lead to the village’s decline.

One day, the man he hired to investigate the matter reported that he saw a baby dragon complaining to a larger dragon that people keep hurting his leg. The mother dragon replied, “They’ll never get through, unless they use copper needles or black dog’s blood.”

The man went to gather the materials, and the next night when the two dragons appeared again, he splattered the blood on the spot where the workers had been digging.

The small dragon screamed in agony, and after causing a massive storm the mother took the baby and flew off. The next day, the villagers woke up to see that their work had been completed. That night, the spirit medium at the village’s Jhensi Temple (鎮西宮) reported that the baby dragon had been injured and needed to take refuge with the temple’s chief deity, Shennong (神農, god of agriculture), adding that it would return to Foshan 60 years later.

As the spirit medium predicted, a banyan tree appeared next to the temple the next day, growing into today’s five-legged tree that resembles a small dragon, with a shrine dedicated to it. From then on, the village’s fortunes declined and young people started leaving the village, leading to today’s situation where more than 45 percent of the population are above 50 years old.

Sixty years later, the religious group I Kuan Tao (一貫道) built a massive complex dedicated to Guanyin on Foshan, fulfilling the prophecy. Chang concludes the tale here, a speckless, monumental complex that greatly contrasts with the crumbling brick structures back in the village.

“We listened to these stories like they are legends, but they can still be traced to some facts,” Chang says, adding that much can be deduced through these truths.

A prime example is one that involves a woman who allegedly lived in a nearby village that no longer exists. Chang found evidence that there was once a village there as the people farming that area reported finding roof tiles scattered through the fields. From the geography and irrigation patterns, he deduced that this village could have been Guoyihou’s former site, which was abandoned. He notes that the village center continues to shift toward the same direction as old structures age and new ones are built.

“We are able to infer all of this through the legend,” he says.

ANCIENT STELES

Aside from the surreal, Chang’s team is serious about preserving the area’s history.

Three objects from the village can be traced to the late 1600s: Jhensi Temple, a stele by Chen’s grave and another stele by the grave of Chiang Feng (蔣鳳), a commander under Koxinga. The latter stele is in the collection of Taipei’s National Museum of History.

The streets of Guoyihou appear to be mostly deserted during the day, with the occasional old person cycling by. Chang seems to know all of them, cheerfully waving as they pass.

The Jhensi Temple lies at an intersection near the village center, near a convenience store resembling a 7-Eleven, which appeared to be closed. The temple looks pretty ordinary, but Chang says it is the oldest in Taiwan dedicated to Shennong. On a wall are dusty old photos dating back to the 1800s, including a news article about how Shennong’s beard grew 15cm with no human interference.

Chang says that this temple is unique due to its medicinal divination lots, where people who are not finding much help from a doctor would throw divination blocks and draw a recipe — usually something mild; a sample recipe contains soybean coat, seven-lobed yam rhizome, sage and rock sugar.

Temple keeper Chang Huang-hui (張煌輝) says that people still regularly visit for the medicinal lots. The local traditional medicine shop is required to provide the ingredients for free, he adds.

Other historic steles had to be rescued or rebuilt, including one from the late 1700s warning people against occupying public land and kidnapping cows for ransom. Chang Chia-cheng and a group of elementary school students found it in 2004 during a field trip, broken in half in a vegetable garden. Today it has been restored and returned to its proper place in the plaza of Jhensi Temple.

Another stele commemorates the visit of Japanese prince Yoshihisa, who reportedly stayed a night in Guoyihou while leading his troops against Taiwanese resistance in 1895. He is said to have been injured when he arrived and died shortly after, the first Japanese royal to perish outside the country.

This stele become the entrance sign of the now-defunct Foshan Orphanage. Chang examines the stele, trying to make out the faded characters, adding that it’s fortunate that the years of misuse had not completely damaged the text. But the history expert they consulted warned them against moving the stele back to its original spot as it was made of fragile sandstone and could fall apart.

“The stele stands alone here, looking completely out of place compared to the scenery and buildings around it,” Chang says. “It’s a pretty dreary situation.”

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Even today, legends continue to form around Guoyihou. In 2010, the Chinese-language China Times ran a report on college student Lin Yu-hsuan’s (林雨璇) encounter with Chen’s ghost while passing through the area. The ghost asked her to enlist her father’s help in tidying up the long-neglected gravesite. Even though Lin’s father could not find anything on the family’s relation to Chen, he agreed to fulfill Chen’s wishes anyway.

Chang recounts this story, as well as that of blind farmer Chang, in a hushed tone near Chen’s grave, as if Chen’s ghost were watching.

But legends and history are things of the past. Guoyihou’s population continues to drop, from 3,460 in 2003 to 2,948 as of last month, according to official census records. Traditions are dying, such as the Chia-ko Array (車鼓陣), an often-humorous folk opera that combines acrobatics and religious troupe movements typically performed by women, which has only three accompanying musicians left — all in their 70s and 80s.

Chang has published a book about the array and is trying to get elementary school students involved in the performances through Lunar New Year celebrations.

With mostly old people who still work full time in the fields, and younger people working long hours elsewhere, recruiting manpower has also been a problem for Chang, as he quips that he’s happy to even get people to attend his events. Government assistance mostly consists of initial funding, with little to no training or follow-up support, and Chang, a lifelong educator, claims to be no expert on community development.

“The main goal of community development is to affect people,” he says. “We started from cleaning up the environment because that’s easily visible. But ultimately we need people involved.”

The biggest challenge for the village, perhaps, is attracting young people to move back and change the aging demographic.

“That’s way further down the road, and I have no answer right now,” Chang says. “I started this project brimming with confidence ... But now, I’m just trying to do what I can.”

新聞來源:TAIPEI TIMES

An example of the Shennong Community Development Association’s beautification project of a formerly overgrown and abandoned lot in Guoyihou Village. Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

This shrine was built to honor the “five-legged” banyan tree that, according to legend, is the embodiment of an injured baby dragon. Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The grave of Cheng Yong-hua, a military adviser to Ming Dynasty loyalist Koxinga, lies in Guoyihou Village. The Qing Empire moved his remains back to China but the grave remains. Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Jhensi Temple in Guoyihou Village provides medicinal lots as well as regular ones. Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times