《TAIPEI TIMES》 Taiwan in Time: Foreign views of French-occupied Penghu

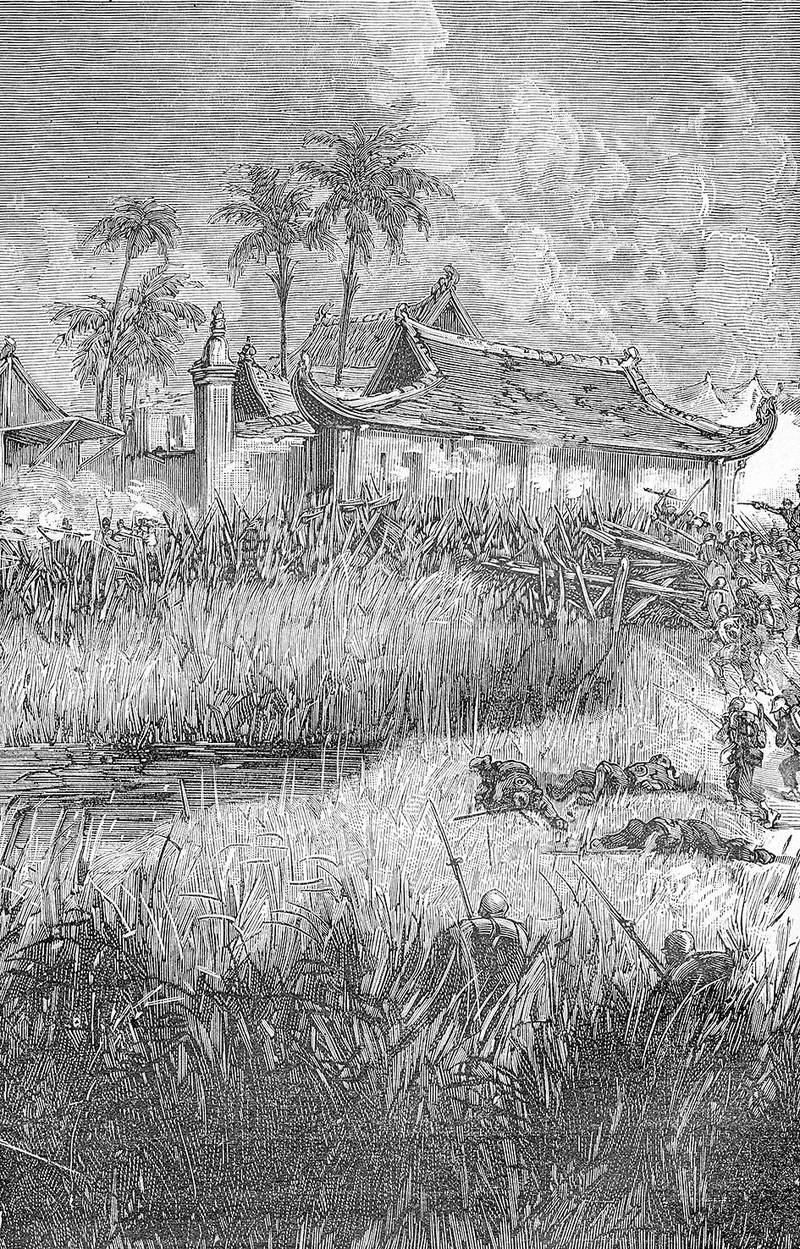

French soldiers pose for a photo with Magong residents during their occupation between March and August 1885. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Several European accounts paint a picture of life in Magong during its several months under the rule of admiral Amedee Courbet

By Han Cheung / Staff reporter

March 29 to April 4

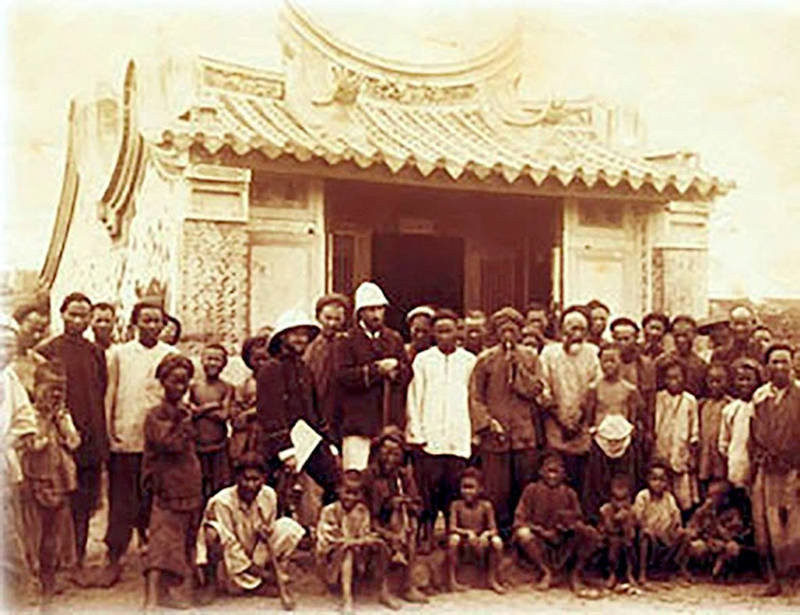

All Rene Coppin could see were burnt, collapsed and cannonfire-riddled houses when he landed in Magong (馬公, then spelled 媽宮), the main settlement of Penghu on April 24, 1885.

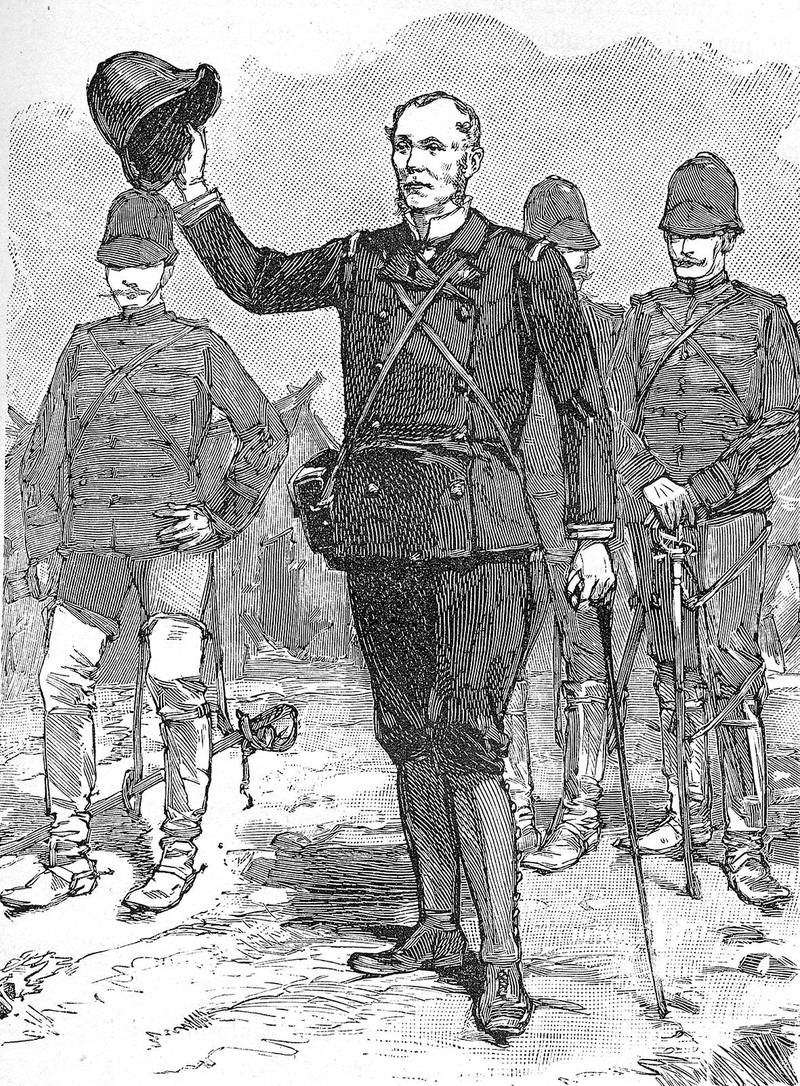

On March 29, French admiral Amedee Courbet led an invasion of the archipelago near the end of the Sino-French War, routing the Qing forces and capturing the town in three days. Coppin was a physician on the cruiser Nielly, and his letters to his mother, translated into Chinese in 2013 by Julie Couderc, provide first-hand information on the condition of Magong under its brief French occupation.

Scottish missionary William Campbell writes in Sketches from Formosa that shortly after the battle, “notifications were issued to inform all who were concerned that what was taking place arose from a quarrel between two nations.”

This would be the third time in history that Penghu got caught up in such a conflict. The Ming Dynasty engaged in a months-long struggle against the Dutch there in 1624, and the Qing Dynasty’s victory over the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning in 1683 paved the way for its annexation of Taiwan the following year.

After failing to capture Tamsui and Taipei despite taking Keelung in 1884, the French forces turned to Penghu to prevent the Qing from reinforcing its troops in Taiwan.

The victory probably didn’t affect the outcome of the war much — in fact, Courbet’s feat went largely unnoticed in France as the nation was more concerned about the collapse of then-prime minister Jules Ferry’s government. Peace talks began shortly after, and the French left Penghu in August.

TOWN IN RUINS

In addition to serving as a physician on the cruiser Nielly, Coppin served as assistant to the chief French physician on Courbet’s warship, the Bayard. He found Magong’s harbor to be beautiful, although the town lay in ruins. Much of it was damaged by French shelling, but the retreating Qing soldiers also engaged in looting and destruction.

He praises Courbet’s campaign, noting that very few Qing soldiers got away. The Qing forts were toppled and all cannons destroyed, and its armory was flattened in an explosion that killed 600 troops.

“The fields have turned into graves, and with each step one could find artillery shells on the ground,” Coppin writes.

Coppin mentions the poor sanitary conditions, noting that Penghu was in the midst of a cholera outbreak and that countless French soldiers succumbed to the disease. Only those who mostly stayed on the Bayard avoided getting sick, although that wouldn’t be the case later.

The warship housed many Qing prisoners, who were brutally executed whenever they were caught trying to escape. Coppin witnessed one of these jailbreaks and participated in the operation to catch the escapees. The two survivors were tied to a stake on the beach and shot dead.

“This is my first time taking part in an execution, and I hope it’s my last,” he writes. “I didn’t have a choice as I was ordered to do so, but I could barely sleep the next evening. In my nightmare, I saw the two Qing escapees tied to the stakes. They were brave and their faces didn’t show any sign of fear.”

Despite violence against prisoners, Campbell writes that things were quite peaceful between the French and locals.

“The tumble-down condition of the buildings did not prevent hundreds of those who fled at the commencement of hostilities from returning, nor lessen their eager desire to earn as many as possible of those clean, Mexican dollars which now streamed in upon the place,” he writes.

The residents did all sorts of jobs for the French at reasonable prices, and spoke highly of Courbet when Campbell visited.

NO FINER COLONY

The book Le Mousse De L’amiral Courbet by a young sailor named Jean L. also details the French occupation of Penghu. According to the Academia Sinica-published Chinese version, the account is “neither historic nor fiction, but should be considered literary reportage.”

Jean L. also marveled at the beauty and scale of Magong’s harbor, and unlike Coppin he was overjoyed to stay in the town despite describing it as ugly and unsanitary. The locals were terrified of the French at first, but slowly relaxed their guard.

“They were no longer afraid of us, they resumed farming and flooded the streets and tried to rip us off whenever they could,” Jean L. writes. “But they’re not bad people, especially compared to those in [Keelung]!”

Apparently, merchants in Keelung gouged the French since they were in a more desperate situation trying to capture Taipei. In another sentence, however, Jean L. calls the people of Penghu “dirty and stupid.”

After almost losing his life to a water buffalo attack, Jean L. befriends a local fisherman, who teaches him about sharks and takes him fishing by moonlight. He tries shark fin, noting that it’s such a prized possession that locals are willing to sell their firstborn son’s inheritance for it. He also writes that the officers enjoyed collecting local arts and crafts, and was especially amused when a French pastor acquired a golden Buddha statue from a Penghu monk.

Jean L. was upset that the French decided to evacuate the archipelago, especially after they spent much effort fixing up the harbor, writing that his country possessed “no finer colony.”

After signing the peace accord, the French began moving their operations from Keelung to Penghu, and the port remained buzzing with foreign activity for the next few months. Courbet tried to persuade his government to keep the archipelago, to no avail.

As evacuation procedures continued, the admiral fell sick and died on June 11. On June 12, all the flags on the Bayard were lowered to half-mast, and Coppin helped preserve his corpse for the journey home. The ship departed Penghu on June 23 to a 19-gun salute, still bearing the scars of its fierce battles against the Qing.

Courbet’s belongings were buried in a gravesite in Magong alongside two French officers. The Japanese hired locals to watch over the site, but it was razed in 1953 to make way for the expansion of Magong High School. A small monument remains today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

新聞來源:TAIPEI TIMES

An illustration of admiral Amedee Courbet in Magong during the French occupation. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This map shows the route of the French invasion of Penghu in 1885. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons